I have two somewhat silly and very tangential connections to Afghanistan. I was born near the Owens Valley's famous Alabama Hills, now used largely as a setting for SUV commercials and occasional science fiction films (Tremors, various Star Trek movies, etc.--in fact, in the recent Iron Man, the site stood in for Afghanistan). Once upon a time, however, this desert of bizarrely shaped granite boulders was the go-to movie set for some real classics, such as Gunga Din (1939) and King of the Khyber Rifles (1953). The "connection" here involves my uncle Art, who was an extra in the latter, and recognizable only as "the first one over the hill" according to my grandmother.

I have two somewhat silly and very tangential connections to Afghanistan. I was born near the Owens Valley's famous Alabama Hills, now used largely as a setting for SUV commercials and occasional science fiction films (Tremors, various Star Trek movies, etc.--in fact, in the recent Iron Man, the site stood in for Afghanistan). Once upon a time, however, this desert of bizarrely shaped granite boulders was the go-to movie set for some real classics, such as Gunga Din (1939) and King of the Khyber Rifles (1953). The "connection" here involves my uncle Art, who was an extra in the latter, and recognizable only as "the first one over the hill" according to my grandmother.When I was a little older, during my mother's stint as a reporter in Taiwan, she had a friend (the only other woman among those who hung out at the Foreign Correspondents Club) whose name now escapes me. But she was an exotic and glamorous figure, tall and grey-haired, and held me rapt at her knee with stories about "Samuel the Camuel" and his adventures in Kabul, where she had long been stationed by one of the news gathering agencies. She once brought me a stuffed camel who then traveled with me until he disintegrated.

So except for these minor elements I have no real claim to having thought much about Afghanistan during my entire life, except when I show images of the Friday Mosque in Herat during my lecture on Islamic Art. But during the past ten years, as news of various incidents has hit the wires, this ancient and rather mysterious country has entered my consciousness on an increasingly more immediate level. Not long ago I heard someone discussing the fact that during the Russian invasion in the '80s, one of the most devastating effects had been the destruction of apricot and pistachio trees and their subsequent replacement with fields of opium poppies.

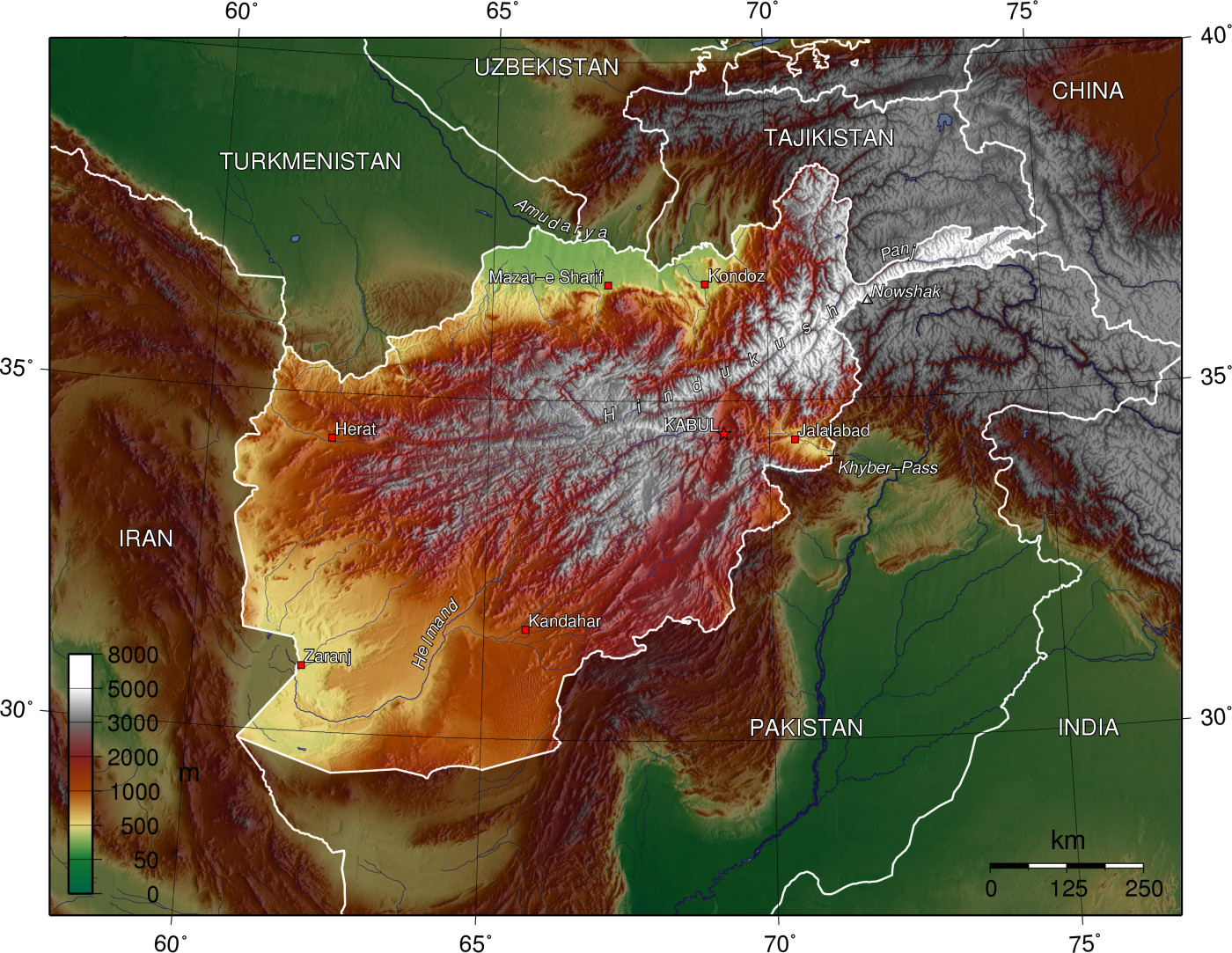

Once known as Ariana, the history of the region we now call Afghanistan reaches back into prehistory, and was almost certainly one of the earliest regions to develop pastoralism and agriculture outside of the Fertile Crescent. Its centrality as a crossroads drew attention from the Medes and Persians, from Alexander the Great, and later from the Mongols--among others. Because it borders on what is now Pakistan, it became important to the British Raj (hence the romance of the Khyber Rifles), and although it became nominally independent in 1919, Afghanistan has been politically battered ever since, except for the relatively stable forty-year reign of King Zahir Shah. Since his overthrow in 1973, the U. S. and Russia have vied for influence, and Afghanistan has become a political volleyball (albeit a very large one).

Once known as Ariana, the history of the region we now call Afghanistan reaches back into prehistory, and was almost certainly one of the earliest regions to develop pastoralism and agriculture outside of the Fertile Crescent. Its centrality as a crossroads drew attention from the Medes and Persians, from Alexander the Great, and later from the Mongols--among others. Because it borders on what is now Pakistan, it became important to the British Raj (hence the romance of the Khyber Rifles), and although it became nominally independent in 1919, Afghanistan has been politically battered ever since, except for the relatively stable forty-year reign of King Zahir Shah. Since his overthrow in 1973, the U. S. and Russia have vied for influence, and Afghanistan has become a political volleyball (albeit a very large one).The Soviet invasion and subsequent ten-year war, as well as U. S. involvement in counter-Soviet groups, succeeded only in politicizing various traditional factions and fomenting the problems that helped lead to 9/11. (For an excellent account of the situation, I recommend Robert D. Kaplan's Soldiers of God.) And now we're getting ready to send even more troops into Afghanistan to help stem the tide that we helped to create.

As Peter Parker suggests on this Reuters film clip, we're on the verge of another Soviet-like debacle. It doesn't appear as if it's going to accomplish much, and so I thought it might be helpful to consider a different strategy: one that many folks are already working on, and that will benefit the Afghans far more than sending more soldiers and robot-bombers into the country.

The most enduring damage inflicted by Russian invaders in the '80s was to the agricultural infrastructure that had traditionally managed to feed the Afghan people despite persistent drought and its paucity of arable land. They bombed fields and irrigation systems, shot livestock, and so completely disrupted the agricultural economy that farmers have since turned to poppy-growing to provide an already over-drugged world with more opium. For a thorough and moving account of the plight of Afghanistan's natural environment, I encourage you to read Afghanistan's Natural Heritage: Problems and Perspectives, by Daud Saba. Given the current situation, the infusion of yet more military traffic into the area seems doomed to failure.

If President Obama wants to shift the hearts and minds of the Afghans away from the Taliban and whatever seems to be attractive about their extreme traditionalism, he must present a more compelling alternative. If we have to send soldiers, it would seem much more profitable (in both a practical and a moral sense) to use them to help protect the people on the ground who stand the best chance of doing the most good: NGOs and aid programs like ICARDA, the Afghanistan Agricultural Initiative, and PEACE who are already working to rebuild irrigation systems, replant trees and traditional crops, reforest hillsides, and enable people to earn their own livings, and take their country back for themselves.

Efforts designed to "bring the Afghan people into the twenty-first century" (whatever that means) need to be put on a back burner, because until these people can feed themselves and have means to a livelihood other than opium-growing, they're going to follow anyone who promises them food and protection from the invader du jour, whether it be Russia, Pakistan, or the U. S.

Even with its history of drought and hardship, Ariana was a land of mountains and deserts interspersed by garden valleys. Nobody would ever claim that it was paradise, but it was, as Daud Saba notes, sustainable. The greatest gift the United States could provide would be to ensure that this ancient land be able to restore itself, and to regain its ability to rely on traditional agriculture, pastoralism, and craft industries to to replace the dessicated valleys, the ruined fields, and the land mines.

Even with its history of drought and hardship, Ariana was a land of mountains and deserts interspersed by garden valleys. Nobody would ever claim that it was paradise, but it was, as Daud Saba notes, sustainable. The greatest gift the United States could provide would be to ensure that this ancient land be able to restore itself, and to regain its ability to rely on traditional agriculture, pastoralism, and craft industries to to replace the dessicated valleys, the ruined fields, and the land mines.Addendum 02/25/09: On the way to school yesterday, I listened to a broadcast of PRI's The World, featuring Marco Werman's interview with Jennifer McCarthy. Her blog, Water Flows, talks about the interview and its aftermath, but it was a nice coincidence to hear this not long after I'd posted the above. She's living in Afghanistan on $1 per day--and it's more than one of those noble social experiments that often end up meaning little. Her experience offers some real insight into the situation in northern Afghanistan.

Photo credits: Orchards in Eastern Afghanistan by "Executioner," topographic map of Afghanistan, Irrigated Farm Fields in Afghanistan by Todd Huffman. All from Wikimedia Commons.

No comments:

Post a Comment