While negotiating my monthly deluge of digital magazines around the cusp of the month, I often save the quarterly Smith Journal to read when I've got time to savor it at leisure. One of those literate compendia of oddities to which I'm mildly addicted (like Cabinet), it comes less frequently than the monthlies--and even less so than The New Yorker, which I now get weekly--and thus requires slow perusal.

I quickly noticed (perhaps because I'm lately attuned to such things) the abundance of articles about dead stuff in this issue. There's so much of it, that a disclaimer of sorts appears on the editorial page:

You could chalk it up to living through these 'uncertain times'--the political turmoil, the 24-hour news cycle, the unseasonable weather harbinging certain environmental collapse. But flicking through the ink-smudged proofs as we corral this thing into something approximating a magazine, I don't think that's quite it. Death, as the platitudes tell us, is an integral part of life; the other side of a coin tossed in the air. Coming to some kind of terms with the fact that we're all headed for the grave seems like a good use of our time on this side of the soil.Indeed. Just last week I was awaiting my latest flirtation with (I hoped) temporary oblivion (general anesthesia), the single scariest event I've faced since the last time I was under the knife nine years ago. This time it was to correct an artefact of the last one, experienced about a year later when I tripped on a garden hose and landed flat on my torso, tearing a small hole in the incision from the valve job. Said tear gradually grew larger over the ensuing years until my GP's PA, my cardio guy, and my swell new surgeon all decided it was time to repair it. So last Wednesday I underwent robotic surgery to do a bit of boro work on my gut.

The Robot's name was Da Vinci. My surgeon, unlike my art history students, was until recently unaware that Leonardo was the artist's use-name. Da Vinci really means "bastard son of a guy from Vinci," which I never tire of telling anyone who will listen, including my rather affable young anaesthesiologist. (When she came in to meet me, I blurted out, "A chick anaesthesiologist! How very cool!")

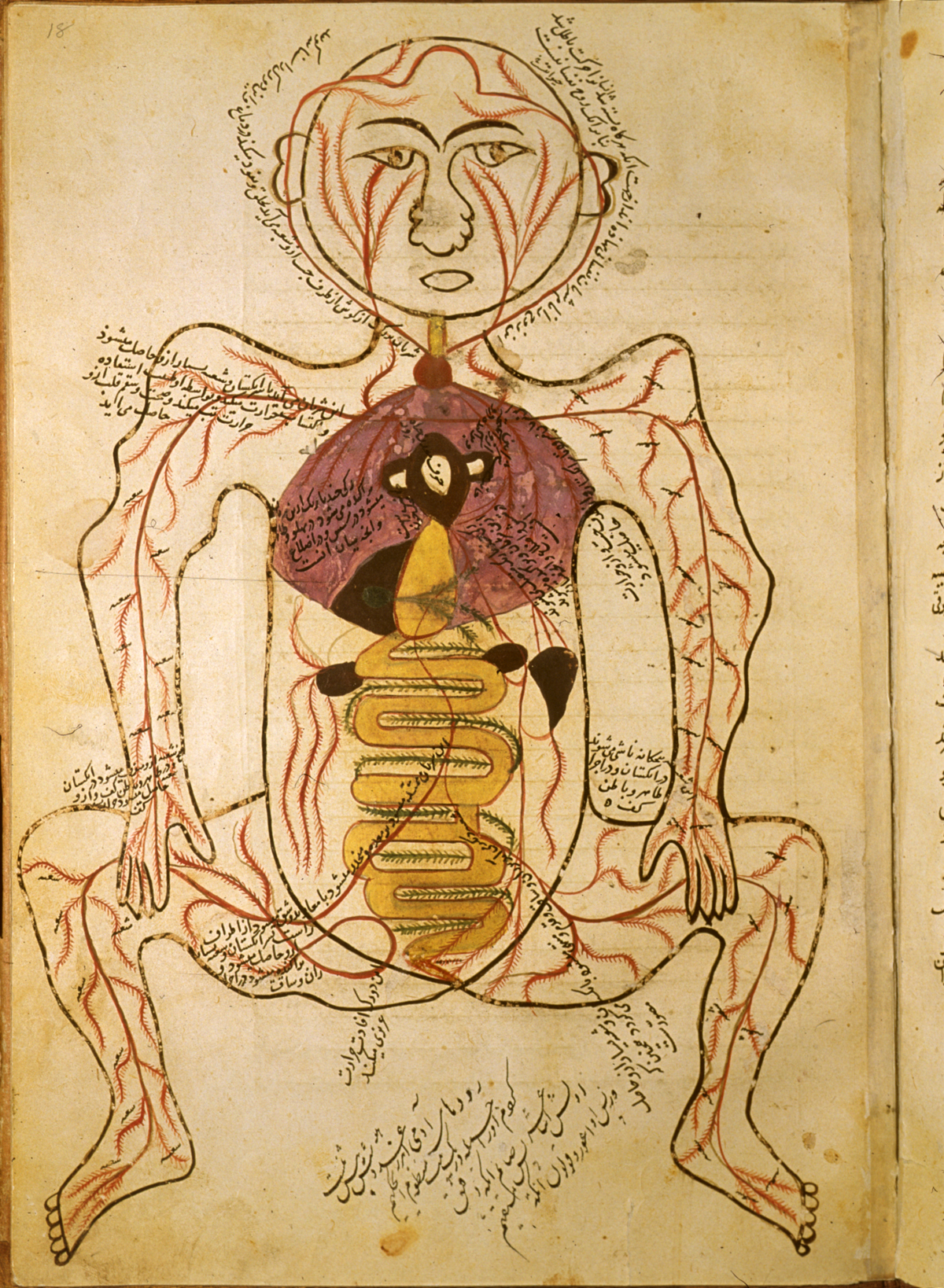

In the run-up to the surgery, which required a CT scan (of which I now own a CD copy of the images--although not as nicely colored as the illustration above), I had plenty of time for musing about the eventual outcome. My main concern was that I am totally unprepared, from both a legal perspective (no will, no advance directive) and in the sense of what the Swedes call "death cleaning." A few months ago I bought the Kindle version of Margareta Magnusson's The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter, in hopes that it would give me some strategies for getting things sorted out now that we've got time for sorting. I don't really want to de-clutter so much as to catalogue, since one woman's clutter is another's Owls Head. But I do want to get a handle on the collections (inspired by the likes of Joseph Cornell, Rosamond Purcell, and Sibella Court), although I'm not sure if I'll get around to doing anything with them except arranging small, artfully-contrived museum exhibits around the house.

Small tremors of terror began to well up into my psyche to the tune of "what if I die under the robotic knife and I leave all this shit for Esther and Ethan and Rod to clean up?"

Instead of actually doing anything about it, though, I took the time to chill out, sit back, and update my Pinterest boards--which are a visual version of my garage (only much tidier and much, much prettier).

In the end, however, I did not die (at least I haven't yet). I did repeat the question I stole from Mal Reynolds in the "Out of Gas" episode of Firefly, to the amusement of no one but by daughter and my husband, and which provides the title for this post. Back in 2009, as I was being wheeled in for valve replacement surgery, I said the very same thing to them, although more spontaneously. Only that time, the nurse who was taking care of me was a Firefly fan and knew the dialogue every bit as well as we did. The last thing I remember as I lost consciousness was the bed's shaking with her laughter as she guided me down the hallway.

My jokes are all old and well worn, even if they have found fresh audiences. I shouldn't have to dig them up again. Documentation and cataloguing of the archives is still to be done, however, and now I won't be able to put it off once the healing is finished. That may take a bit, because although my plumbing seems to be working again, I'm sore and tired and every now and then feel like somebody's going at me with a hot poker. I've got to wear an abdominal binder for a few weeks, and I won't be able to do the full range of Qigong practices I'd followed faithfully during the last three months for at least another three.

The good news is that by week 4 (according to a vast cache of online literature about healing from ventral hernia repair) I should be able to play tennis.

Which will make my Beloved Spouse happy indeed, since I never could before.

Ba-dump-bum.

Image credit: The arterial figure, shown frontally with the internal organs indicated in opaque watercolours. An undated and unsigned copy, probably 15th or early 16th-century. Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān (MS P 19) (The Anatomy of the Human Body)

تشريح بدن انسان by Manṣūr ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf Ibn Ilyās (fl. ca. 1390). MS P 19, fol. 18a. Image at NLM. Available through a Creative Commons license at the Brooklyn College Library.

Note: This is another bit of an art history joke. I used to amuse my students with illuminated manuscripts featuring odd drawings and drolleries of all types. Some of my favorite were from a genre I called "anatomical squats," used to illustrate innumerable ailments in Medieval Arabic medical MSS.

No comments:

Post a Comment